There is a vicious cycle of associated with poverty and mental illness. It is a self-reinforcing circle where poverty is linked to greater incidence of mental illness, and mental illness is linked to a greater likelihood of living in poverty.

A 2005 study looked at the health records of 34,000 patients who were hospitalized at least twice for mental illness over a seven-year period. The study looked at whether or not these patients had “drifted down” to less affluent ZIP codes following their first hospitalization. The study found that poverty — acting through economic stressors such as unemployment and lack of affordable housing — is more likely to precede most mental illness.

A prior post discussed location-based "insights" provided by employment assessment companies like Kenexa and Evolv. These companies believe that a greater distance from the jobsite, lengthier commute times and more frequent household moves should weigh against - or even exclude - job applicants from consideration for employment. As the prior post noted, these insights are generalized correlations, they say nothing about any particular applicant.

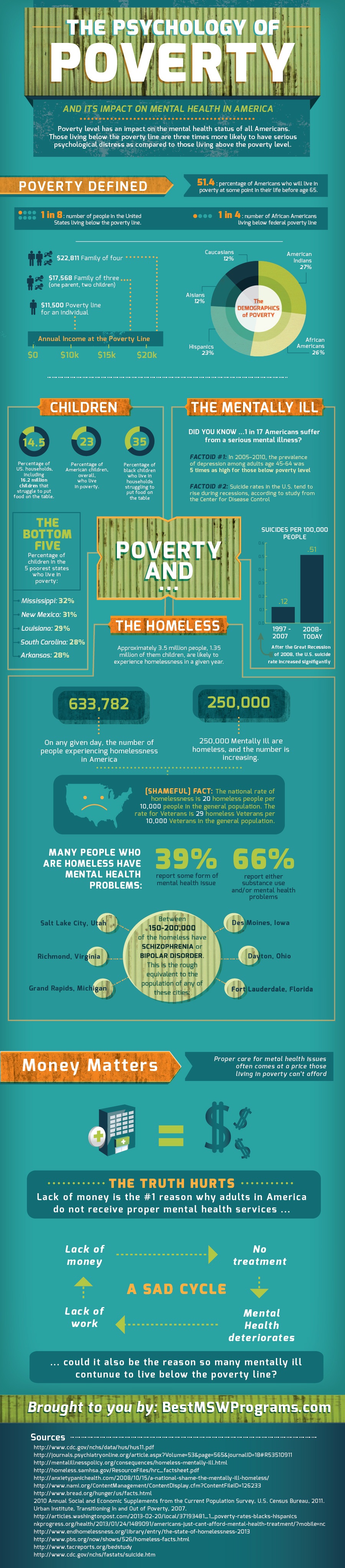

Employers utilizing these location-based "insights" screen out qualified applicants solely because they live (or don't live) in certain areas. Not only do employers do a disservice to themselves by eliminating qualified persons from consideration for employment, the use of these insights discriminates against the poor, who are disproportionately represented by African-Americans and Hispanics. As shown in the graphic to the right, Blacks are more than two-and-a-half times as likely as Whites to live below the federal poverty level. Similarly, Hispanics are twice as likely as Asians to live below the federal poverty level. The federal poverty level in 2010 for an individual was $10,830 and for a family of four was $22,050. The graphic is taken from a 2011 report issued by the National Center for Health Statistics.

This post reprises certain information from the prior post and then discusses how the use of the location-based insights also discriminates against persons with mental illness.

According to a 2011 study by the Center for Public Housing, entitled "Should I Stay or Should I Go? Exploring the Effects of Housing Instability and Mobility on Children," a wide range of often complex forces appears to drive frequent mobility, and residential instability in general — the formation and dissolution of households, an inability to afford one’s housing costs, the loss of employment, the lack of a safety net, lack of quality housing or a safer neighborhood.

According to Kenexa and Evolv, however, the correlation between (A) persons who move more frequently and (B) shorter job tenure is that A causes B. However, a 2011 study by the Center of Public Housing demonstrates that it may well be that (B) shorter job tenure causes (A) persons to move. As shown in the table below, taken from the 2011 study, 76% of involuntary moves were a result of job loss. The second highest factor precipitating involuntary moves is mental health problems.

One of the most consistently replicated findings in the social sciences has been the negative relationship of socioeconomic status (SES) with mental illness: The lower the SES of an individual is, the higher is his or her risk of mental illness.

Employers utilizing these location-based "insights" screen out qualified applicants solely because they live (or don't live) in certain areas. Not only do employers do a disservice to themselves by eliminating qualified persons from consideration for employment, the use of these insights discriminates against the poor, who are disproportionately represented by African-Americans and Hispanics. As shown in the graphic to the right, Blacks are more than two-and-a-half times as likely as Whites to live below the federal poverty level. Similarly, Hispanics are twice as likely as Asians to live below the federal poverty level. The federal poverty level in 2010 for an individual was $10,830 and for a family of four was $22,050. The graphic is taken from a 2011 report issued by the National Center for Health Statistics.

This post reprises certain information from the prior post and then discusses how the use of the location-based insights also discriminates against persons with mental illness.

Reprising "From What Distance is Discrimination Acceptable?"

The assessment company Kenexa, purchased by IBM in December 2012, will test approximately 40 million applicants this year for hundreds of clients. Kenexa believes that a lengthy commute raises the risk of attrition in call-center and fast-food jobs. It asks applicants for call-center and fast-food jobs to describe their commute by picking options ranging from "less than 10 minutes" to "more than 45 minutes."

The longer the commute, the lower their recommendation score for these jobs, says Jeff Weekley, who oversees the assessments. Applicants also can be asked how long they have been at their current address and how many times they have moved. People who move more frequently "have a higher likelihood of leaving," Mr. Weekley said.

As a consequence, Kenexa clients will pass over qualified applicants solely because they live (or don't live) in certain areas. Not only does the employer do a disservice to itself and the applicant, it increases the risk of employment litigation, with its consequent costs.

Distance From Jobsite

A New York Time article from earlier this year, "In Climbing Income Ladder, Location Matters," reads, in part:

Stacey Calvin spends almost as much time commuting to her job — on a bus, two trains and another bus — as she does working part-time at a day care center. ...

Her nearly four-hour round-trip [job commute] stems largely from the economic geography of Atlanta, which is one of America’s most affluent metropolitan areas yet also one of the most physically divided by income. The low-income neighborhoods here often stretch for miles, with rows of houses and low-slung apartments, interrupted by the occasional strip mall, and lacking much in the way of good-paying jobs.

This geography appears to play a major role in making Atlanta one of the metropolitan areas where it is most difficult for lower-income households to rise into the middle class and beyond, according to a new study that other researchers are calling the most detailed portrait yet of income mobility in the United States.

The dearth of good-paying jobs in low-income neighborhoods means that residents of those neighborhoods have a longer commute.

Housing Mobility

As shown in the table below, poor and near-poor families tend to move much more frequently than their higher income neighbors and the general population.

According to a 2011 study by the Center for Public Housing, entitled "Should I Stay or Should I Go? Exploring the Effects of Housing Instability and Mobility on Children," a wide range of often complex forces appears to drive frequent mobility, and residential instability in general — the formation and dissolution of households, an inability to afford one’s housing costs, the loss of employment, the lack of a safety net, lack of quality housing or a safer neighborhood.

Correlation Is Not Causation

When two variables, A and B, are found to be correlated, there are several possibilities:

- A causes B

- B causes A

- A causes B at the same time as B causes A (a self-reinforcing system)

- Some third factor causes both A and B

The correlation is simple coincidence. It is wrong to assume any of these possibilities.

According to Kenexa and Evolv, however, the correlation between (A) persons who move more frequently and (B) shorter job tenure is that A causes B. However, a 2011 study by the Center of Public Housing demonstrates that it may well be that (B) shorter job tenure causes (A) persons to move. As shown in the table below, taken from the 2011 study, 76% of involuntary moves were a result of job loss. The second highest factor precipitating involuntary moves is mental health problems.

Socioeconomic Status and Mental Illness

One of the most consistently replicated findings in the social sciences has been the negative relationship of socioeconomic status (SES) with mental illness: The lower the SES of an individual is, the higher is his or her risk of mental illness.

As an example, for the period from 2005-2010, the Centers for Disease Control found that among adults 20–44 and 45–64 years of age, depression was five times as high for those below poverty, about three times as high for those with family income at 100%–199% of poverty, and 60% higher for those with income at 200%–399% of poverty compared with those at 400% or more of the poverty level.

As noted above, the federal poverty level in 2010 for an individual was $10,830 and for a family of four was $22,050.

People who live in poverty are at increased risk of mental illness compared to their economically stable peers. Their lives are stressful. They are both witness to and victims of more violence and trauma than those who are reasonably well off, and they are at high risk of poor general health and malnutrition. Similarly, when people are mentally ill, they are at increased risk of becoming and/or staying poor. They have higher health costs, difficulty getting and retaining jobs, and suffer the social stigma and isolation of mental illness.

Thousands of employers utilize pre-employment assessments provided by companies like Kenexa and Evolv, whose location-based "insights" discriminate against lower-income persons. According to a 2001 study, lower income Americans had a higher prevalence of 1 or more psychiatric disorders (51% vs 28%): mood disorders (33% vs 16%), anxiety disorders (36% vs 11%), and eating disorders (10% vs 7%). Consequently, pre-employment assessments using these location-based "insights" violate the Americans with Disabilities Act by illegally screening out persons with mental illness.

.